“In the game of baseball, Home is rugged, fixed into the earth, trod upon, but precious. Home is an altar. It is protected. It is defended. It is cleaned. Home plate represents the sacred amidst the profane.” Abe Stein, “How Home Plate Lives Up to Its Name,” The Atlantic, March 31, 2014

“We should all put our shoulder to the wheel and see to it that our city has a park, where children may go to recreate.” The editor of the Snohomish County Tribune, April 1, 1921, was inspired by the volunteer action of residents Herb Halterman, R. E. Main and F. V. Bowen who improvised a baseball diamond out of a vacant lot alongside the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad on the east side of town in the spring of 1921.

Leading up to the metaphor of manual labor the editor had a specific list: “This park should be fitted up with swings, rings, teaters and everything that goes to make a playground for the children.” Immediately, the three men formed the Snohomish Play Ground Association with the “aim to equip the property in the vicinity of the N.P. tracks with all kinds of apparatus for the amusement of the children” — but it depended on the sale of season tickets for the Snohomish Baseball Association which had been taken over by the Play Ground Association. (Tribune, April 29, 1921)

As the world turns, there would no playground apparatus until the early 1990s when members of the Tillicum and Snohomish Kiwanis put their collective shoulders to the wheel and built the playground we see today. (“Kiwanis urge city move on Averill,” Tribune, June 19, 1990.)

It’s not clear when the field was officially given the name “Averill” — perhaps it was simply adopted when Earl Averill left the hometown team to play with the Cleveland Indians in 1929 — where he “became the first rookie in major league history to score a home run his first-time at-bat.” (Tribune, April 7, 1999.)

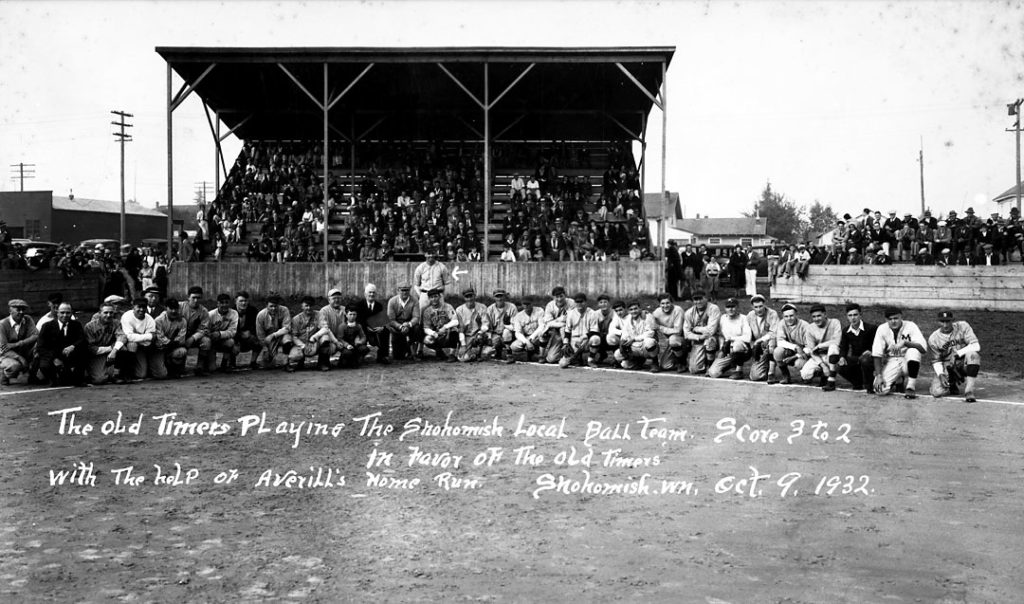

“Podunk” Averill would return home to play with the Old Timers in the annual fundraising game against the Garden City Boys, Snohomish’s current team. The Old Timers were kept in line by Herb Ness, the manager who discovered Averill back in the day. Courtesy Snohomish Historical Society

“Know How to Build a Pool?” the Tribune asked in its October 9, 1947 issue — but it was not until July 7, 1970, that its front page boasted: “Ground Broken for Moe Memorial Pool.” The headline stretching the width of the paper was accompanied with a large photo of Lila Moe holding a shovel, her right foot in place ready to push it into the ground. Her late husband, Hal Moe (1916-1968), was the beloved principal then superintendent of Snohomish Schools who died around the time the city was tearing down the grandstand (pictured above) to make room for the pool. The baseball diamond was eventually reestablished at the southwest end of Averill Field, but a smaller layout intended for Little League play, while plans developed to install a full-size diamond in new parkland alongside the Pilchuck River.

When two bond issues put before city voters to cover the outdoor pool failed, the Hal Moe Pool Working Group recommended that the school district take over the ownership and operation of the pool from the city. Bringing in voters from the school district, a $1.4 million bond issue passed in a September 20, 1988, primary election — a successful outcome following months of discussion between citizens, school and city representatives. Under terms of the agreement, the city transferred ownership of the pool and 20 feet of the north end of Averill Field to the district with “a guarantee that the public will have access to the pool no less than 65 percent of the time that it is open.” (Tribune, August 8, 1988.)

Plans were to open the covered pool with new locker rooms in the fall of 1989; meanwhile, a March 3, 1989 editorial in the Tribune read: “Time to consider Averill Field sale.” Seems it was in response to a city planning commision decision “to not consider a city staff request to designate the southern half of Averill Field for commercial use.” City Manager Kelly Robinson felt the remaining property was undersized and underused and selling it for commercial use “the city would have money to buy enough land in the valley to replace the field many times over, and put the balance into a trust fund for city parks.” The editorial points out that “some doubt Averill Field can be sold because of a clause attached to the deed which specifies the land can only be used for recreation purposes”– the first mention of the deed that 25 years later became the emotional protest tag: “Restore the Deed!”

“City leaders agree to keep Averill Field.” Councilwoman Ann Averill, daughter-in-law of the field’s namesake was quoted in the Tribune’s April 11, 1990 issue: “I think the city needs to preserve a green space for the people who live here now and the people who come after.” The field, including the pool in the process of being covered, is sandwiched between the now Burington Northern railroad tracks and Pine Avenue, west to east, and between 3rd Street and 2nd, north to south.

The property was deeded to the city in 1922-24 by the three men whose volunteer muscle started the wheel turning with the restriction that it be used for “playground purposes only” — the irony is that the Play Ground Association never did install a playground as baseball dominated the use of the field, to the timid chagrin of some citizens. Even Councilwoman Averill suggested the council arrange for experts to evaluate if the field is still practical for playing baseball. At the time, the two-acre site was being used for a variety of sports activities and the annual Kla Ha Ya Days carnival.

The grand opening of the Snohomish School District’s newly covered facility was greeted, on one hand, by neighboring merchants “predicting parking problems” reported the Tribune, June 20, 1990, which has a solid history of stirring the pot on parking issues in Snohomish. In 1991, the city council accepted the Park Board’s recommendations for Averill Field, explained by the late Bill Blake in the Tribune’s December 11, 1991 issue:”Planned improvements include a playground area for small children, picnic tables for families, an exercise area geared toward seniors and a new field for baseball and football.”

“Council approves youth center at Averill Field,” announced the Tribune’s September 27, 2000 issue. “The Snohomish City Council voted 5-1 last week to locate a youth center and skate park at Averill Field.” Howard Averill, son of Earl Averill, said he opposes the change because “it would do away with his father’s memory.” Part of the council’s action is to designate the baseball field at Pilchuck Park as Averill Field, “and directed staff to contact the Baseball Hall of Fame and inform the agency of the change and indicate that Averill Field is now a standard-size baseball field.”

Pictured from/at Home Plate!

The Snohomish School District’s boarded up Hal Moe Facility was sold back to the city in 2013, destroyed on May 14, 2018, and the site is now a field of new grass. This post is research for a proposed exterior interpretative sign located near the parking lot. The sign will feature a large photograph of the 1932 Old Timers Game pictured above, a brief timeline of the Hal Moe Memorial Pool and the interactive activity of locating home plate hidden in the new grass close to its original position!

. . . .