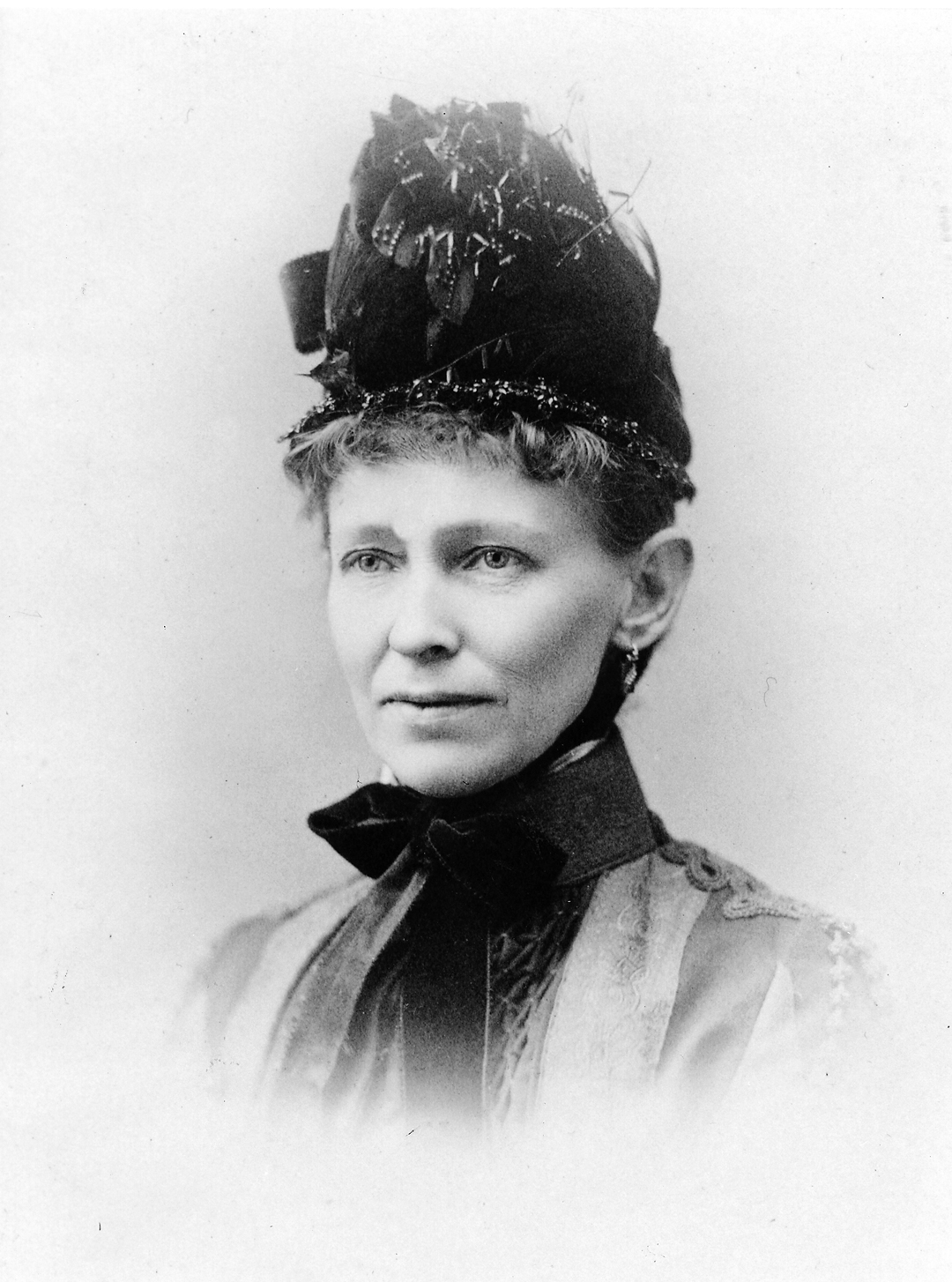

On the last day of April 1865, Mary Low Sinclair and her one-month-old son, Alvin, board the small, unfinished steamer Mary Woodruff in Port Madison, Kitsap County, for a journey across Puget Sound and up the Snohomish River to a place called Cadyville, where her husband, Woodbury Sinclair (1825-1872), has purchased the Edson T. Cady claim that previous December. Mary remembers the day of her arrival in an article published 46 years later in the November 24, 1911, issue of the Snohomish County Tribune. She does not mention the fact that she was the first Caucasian woman to take up permanent residence in the place that was to become Snohomish City. She also fails to note that even by 1911, she is considered to be the founder of education in Snohomish by opening her home as the first classroom. Plus, she skips over the intriguing fact that by learning the native languages of the area, she served as a translator for visiting officials and journalists. The last recorded event was two years before her death, at 79 years of age, when she helps a reporter from Seattle’s Post-Intelligencer interview Snohomish’s famous Pilchuck Julia.

Cadyville, 1865, the first photograph of the settlement that was renamed Snohomish by the Fergusons and Sinclairs in 1871. Ferguson’s Blue Eage saloon is pictured on the left, while the Sinclair store (and first classroom) is on the right. The structure is the center was an unnamed wharf building. Some accounts indentify the man in the foreground as Woodbury Sinclair.

Cadyville, 1865, the first photograph of the settlement that was renamed Snohomish by the Fergusons and Sinclairs in 1871. Ferguson’s Blue Eage saloon is pictured on the left, while the Sinclair store (and first classroom) is on the right. The structure is the center was an unnamed wharf building. Some accounts indentify the man in the foreground as Woodbury Sinclair.

A Clearing in the Woods

Born to John N. Low and Lydia (Colburn) Low in Bloomington, Illinois, on December 11, 1842, Mary and her family were members of the Denny Party that arrived at Alki Point in 1851. Many of the Denny Party became the first settlers of Seattle. The Lows, however, settled in Port Madison, Kitsap County, where Mary worked as a teacher, and ended up marrying her boss, the school district clerk, and lumberman Woodbury Sinclair, on March 4, 1862. Two years later, Woodbury found himself in Cadyville where he purchased the namesake’s claim on the north bank of the Snohomish River. The purchase included a small shack that Woodbury and a partner named William Clendenning planned to open as a store catering to the local loggers.

Mary, their infant son and the household goods arrived on May 1, 1865, which she described in her 1911 remembrance:”As the steamer landed at the gravel bank near the foot of Maple Street, a small clearing appeared in the otherwise unbroken timber. The town consisted of a rough log house on the bank in which supplies were stored. The store farther back, was a twelve by sixteen-foot shack. The old building still standing (1911) at the corner of Maple and Commercial Streets, without windows, doors, or floor, in time was used for the store, with living rooms in the back.”

The infant Alvin died 20 days after Mary’s arrival.

“There was no time to be lonesome …”

Mary’s remembrance continues: “There was much to do, but the pioneers were hustlers and could turn their hands to anything — no specialists in those days. The women, young and hopeful, fearing neither danger or privation, soon began to make things look homelike. A large fireplace assisted considerably in clearing the dooryard, in which later bloomed old-fashioned flowers — Sweet Williams, Marigolds and Hollyhocks. There was no time to be lonesome; frogs sang cheerily in the nearby marshes; mosquitoes kept the people busy building smudges. Wild game was plentiful. The Indians brought venison, wild ducks, fish and clams. Also the ranchers from Snoqualmie Prairie brought delicious hams and bacons of their own curing.”

A second son was born on November 14, 1866, who they named Clarence Wood Sinclair, and he lived to become a popular captain of the favorite steamship Nellie in the 1870s. Mary notes in her 1911 article: “For two years there was no regular steamer outside, and the only fruit available was wild berries. But living was cheap and good, and not a butcher shop in forty miles. The Indian wives of the ranchers made sociable calls on their white neighbors, conversing in mingled Boston, Chinook, and Siwash Wa Wa (talk).”

Mabel “May” H. Sinclair was born on April 28, 1869, and lived until 1935.

The First Cemetery

In 1872, Mary, age 29, with two children, lost her husband Woodbury to death from unknown causes. He was 46 years of age. Just two months earlier they had filed a plat of their claim on the east side of a growing town — now officially named Snohomish City. First, Second and Commercial Streets were parallel to the river, with cross streets named, Cedar, Maple, State, Willow, and Alder. They also sold the original store building, which they had turned into the Riverside Hotel. The hotel featured rooms surrounding a large hall on the second floor that was used by the community for meetings, dances, church services, weddings, court proceedings, and even funerals.

At Woodbury’s death, the Sinclairs were in the process of donating three acres on the eastern edge of their plat, alongside the Pilchuck River, to establish the county’s first graveyard. As the story goes, there was an accidental death of a young Caucasian woman the previous year, which left the frontier community helplessly aware that they had no burial ground — no proper place for a proper lady to rest in peace.

So negotiations with the Sinclairs were in progress when Woodbury passed away on June 5, 1872, leaving his widow — acting as guardian of her children’s estate — to successfully complete negotiations with the newly formed Snohomish Cemetery Association in 1876. (This was done just in time to bury 17 children claimed by an epidemic called “black diphtheria” the following year.)

Mary ordered a headstone of white marble, standing some three feet tall, to create a memorial for Woodbury in the new cemetery, where she also moved the remains of her infant son Alvin and added those of her second son Clarence in 1905, who died from a sudden illness. Mary died on a Sunday, June 11, 1922. She was 79 years old, still living in her home on Pearl Street and still active. She was cremated in Seattle, and, according to sketchy records dating from the 1940s, her remains were included in the family plot in Snohomish’s first cemetery.

The Missing Memorial

The Catholic Church founded the second cemetery in 1895; but the largest cemetery today was established in 1898 by the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War Veteran’s group, simply referred to as the GAR — both were located outside of town. Over the years, the picturesque cemetery alongside the river, framed by a white picket fence, was no longer needed for the newly dead, and so became neglected and eventually referred to as the “Indian Cemetery.” Consequently, not enough attention was paid in the 1940s when the Washington State Department of Transportation claimed that all of the pioneer graves had been moved to other cemeteries, when they extended 2nd Street north, cutting the historic cemetery site in two. There is no record of the Sinclair remains being moved to the GAR, nor those of Mary’s parents, the Lows, who had moved to Snohomish shortly after Woodbury’s death. Only his faded white headstone, the centerpiece of the Sinclair memorial, was found in the abandoned cemetery and it was rescued by the Snohomish Historical Society, where it has held a predominant position in their display of a pioneer graveyard since the late 1980s.

. . . .

More articles commissioned by HistoryLink.org:

Snohomish — Thumbnail History

Snohomish: Historic Downtown Cybertour

Snohomish incorporates as a city of the third class on June 26, 1890.

The Eye reports Gilbert Horton’s floating photography gallery to be in Snohomish on May 29, 1886.

Eldridge Morse dedicates the Snohomish Atheneum on June 5, 1876.

Snohomish County Tribune supports demolition of the old county courthouse portion of Snohomish High School in an editorial on June 16, 1938.

. . . .